|

| Maggie Gyllenhaal and Jeff Bridges in Crazy Heart |

Besides gospel, there is probably no other musical genre in American culture that is so devoted to the quest for roots, or the deep desire for personal transformation, than country music. So when the boozy, destitute country-and-western singer Bad Blake (Jeff Bridges) in

Crazy Heart sings “I used to be somebody, but now I’m somebody else,” he carries in his voice those ghosts on the lost highway that carried singers like Hank Williams and Townes Van Zandt. (Speaking of gospel, Blake may also be carrying the ghost of Thomas A. Dorsey who wrote “Peace in the Valley,” a song about transcendence that drew the interest of both Johnny Cash and Elvis Presley where, in the song, the singer hopes to “be changed from this creature that I am.”)

Crazy Heart is a movie about people who live in songs, trying to find both the roots of their pain, and the seeds of their own salvation within them. Based on a novel by Thomas Cobb, director Scott Cooper doesn’t do anything startlingly new in terms of storytelling, but he does bring a fresh interpretation to a familiar tale: the redemption of the washed-up artist. It also helps that Cooper has Jeff Bridges at the helm. Looking as bleary as a sleep-deprived Kris Kristofferson, Bridges gives a soulful, yet dry and witty performance as a forlorn singer whose wasted life is at odds with his songwriting talent.

The story follows Blake as he hits the road doing concerts in bowling alleys, or seedy bars, and playing to older, nostalgic folks. They hope to connect to the man whose songs once became an indelible part of their lives. Blake knows that he can’t live up to that image so, although he never misses a show, he makes his participation in them vague and uncertain. (In one funny scene, he departs midway through a song to barf in a back alley before rejoining the group for the tune’s conclusion.) While Bad Blake performs in small towns with pick-up groups (who once admired him), his protégé Tommy Sweet (Colin Farrell), who sings Blake’s songs, sells out huge arenas and records hit albums. Sweet has had the success that continues to elude Bad. But Blake has grown used to dives and middle-aged groupies, hiding his bitterness in a bottle, until he meets Jean (Maggie Gyllenhaal), a reporter for a Santa-Fe newspaper. Jean is a single-mom who loves country music – and the songs of Bad Blake – and she wants to do a feature piece on him. But rather than discussing his past, Blake sees a possible hopeful future in this grounded, level-headed beauty. At first glance, he remarks, in the spirit of a typical country lyric, “I want to talk about how bad you make this room look.”

Crazy Heart is about how this bond between them, where they share the lonely, hurtful pining in Blake’s songs, can’t create a stable life when the singer is a barely functional alcoholic. But that’s where Crazy Heart is most original. If Blake can’t transcend the life he sings about in his songs, Jean hopes to find in the man the tender vulnerability she hears in his compositions. The film is basically about how popular music sometimes connects with us so strongly that we hope the artist is the person that we hear in their work. That’s why the romance between this solid working mom and this older broken down man is both believable and poignant – and also, why it can’t truly work. It can only inspire another aching lyric in another hurtin’ country song.

While it’s no secret that Jeff Bridges is one of our great actors, what makes him great is his ability to create distinctly personable portraits without a shade of self-consciousness in his acting. (When he does become self-conscious, as in his ridiculous caricature of the director in George Sluizer’s pointless American remake of The Vanishing, he comes across much worse than a more stylish actor might.) Maggie Gyllenhaal is a perfect match for Bridges since she plays Jean’s romantic longing close to the ground. She has no illusions about Blake, only a desire for something resembling what she loves most in his songs, so there is nothing self-destructive in her yearning. Although it’s a small role, Colin Farrell plays a Garth Brooks prototype without a hint of vanity. Tommy Sweet knows that he’s become a huge success because of Blake’s songs, so Farrell doesn’t turn Sweet into a conventional adversary. While the music in the film is composed mostly by T Bone Burnett, Ryan Bingham and Steven Broder, Bridges and Farrell do all their own singing and it brings a documentary naturalism to their performances.

Crazy Heart was co-produced by Robert Duvall (who has a minor part here) so the picture suggests something of the earlier Bruce Beresford movie Tender Mercies. But that film was so arid and minimal that Duvall’s alcoholic singer always seemed at a remote distance. (His stoic pain was depicted as a badge of integrity.) Crazy Heart is much looser and less formal, without the fundamentalist armour of Tender Mercies. The mercies in Crazy Heart instead are transitory, usually fragile, and much like the songs Bad Blake sings in his desire to find a way home.

-- January 16/10

“I have had enough serious interest in the products of the ‘higher’ arts to be very sharply aware that the impulse which leads me to a Humphrey Bogart movie has little in common with the impulse which leads me to the novels of Henry James or the poetry of T.S. Eliot…To define that connection seems to me one of the tasks of film criticism, and the definition must be first of all a personal one. A man watches a movie, and the critic must acknowledge that he’s that man.”

--Robert Warshow,

The Immediate Experience, 1955.

We seemed to have come a slippery distance from the time when critic Robert Warshow eagerly expressed curiosity about an impulse, or a justification to make a connection between what is often deemed “high culture” and “low culture.” One look at the TIFF Cinematheque Best of the Decade list tells you that there is no desire, or curiosity, to connect with anything but their own church of refined taste. This is why it is really immaterial to discuss what’s on their list of the best films of the past decade. In examining their choices, I’m sure that we can all find things we love (The Gleaners and I, Yi Yi), things we dislike (Syndromes and a Century, Caché), even things we didn’t see and perhaps might want to (Songs from the Second Floor). What is more important is to discuss what isn’t on it – and why.

That question seemed to elude many of the critics who wrote about the series. It’s often been said that the political media has become self-serving and fawning rather than skeptical when it comes to covering politics. But I’d have to extend that view also to our coverage of the arts. The write-ups on the Best of the Decade list revealed a true dearth of critical thinking. What we got instead was friendly consumer reports with enough celebratory bunting and balloons to fill a convention hall. To be critical doesn’t mean necessarily panning the event. I’m speaking actually of pieces that ask thoughtful questions about just what this series represents and maybe why. But I’m afraid that as the gulf between “high culture” and “low culture” has grown wider over the years, the line between criticism and consumer reporting has also narrowed dramatically. But I sense something else going on here as well. The list, which calls itself an ‘alternative,’ is out to make a statement. But it’s not one that sets out to create bridges between the best of “high art” and the best of “low art.” It’s instead about drawing lines in the sand and guarding the gates against the commercial philistines who dare drag dirt into their living room. The Best of the Decade list is not an open and expansive invitation to film lovers; it’s a calling to a hermitage, a hushed seminary for film theorists to worship in.

Over the past few decades, theory began to dominate campuses where many liberal arts scholars and writers have studied. Instead of the more expansive criticism once extolled by cultural critics like Leslie Fiedler, Pauline Kael, Norman O. Brown or Herbert Marcuse, they were replaced by the chilly, detached and cerebral musings of post-structuralists like Derrida, Foucault and Lecan. Theory began sounding the death knoll of criticism. Where criticism teaches you how to think, theory tells you what to think. To be critical means to be in flux, where you’re often forced to struggle with intuition and knowledge, in order to seek some understanding of the truth. “A man watches a movie, and the critic must acknowledge that he’s that man,” as Warshow wrote. Criticism leaves you open to experience – wherever it comes from – to expand your base of knowledge, so that you’re always questioning assumptions. Theory offers you a secure, ready-made solution where you merely gather data to support it (and ignore inconvenient little realities that might refute it).

Many of the movies on the Best of the Decade list are a theorist’s paradise. For instance, if you closely look at their few concessions to American “commercial” fare (

A History of Violence,

The Royal Tenenbaums, and

Far From Heaven) they’re not included because of their dramatic content. Dramatically speaking,

A History of Violence is barely a coherent story. But theoretically, I suppose, you could sum it up as “the return of the repressed.”

Far From Heaven is not really a dramatic rendering of Fifties suburban America. It’s more the movie equivalent of a University position paper on Fifties Hollywood melodramas. But I think that’s what the film curators love it for, the picture’s overtly self-conscious and cerebral tone. Some argue that this list is deliberately exclusive so audiences can experience and discover rare films that never get the attention commercial fare does. But if that’s true, why then isn’t a great director like Jan Troell (

As White as in Snow,

Everlasting Moments), whose films audiences rarely ever see, represented by even a single one of his movies from this past decade? It’s a simple answer. As a lyrical, poetic dramatist, he doesn’t show the formal rigor necessary to earn a seat on their pantheon of major artists. When critic Pauline Kael and Susan Sontag died this past decade, guess who was given a tribute at the Cinematheque? Sontag, with her disdain of popular culture, was by far the favoured choice, unlike Kael who could love Renoir as equally as she did The Ritz Brothers. Isn’t it possible that perhaps both were worthy of the honour? Not if your lines of demarcation separate the artiste from the populist.

There’s no question that what constitutes mass culture today is troubling. When

The Dark Knight is considered cutting-edge and

Up in the Air is being discussed as if it’s a thoughtful tome on our times, it’s maybe tempting to seek shelter with those guardians of high culture. But, for me, despite the mindless product of mass culture, movies have always been the most democratic art form. Everybody goes to the movies. (It’s a claim that you unfortunately can’t make for opera, art galleries, or poetry readings.) Part of the reason for the huge of appeal of films is that they combine and draw upon the essence of all of the arts. Movies can be equally enjoyable as trashy fun, or they can be sublime works that stir you for decades. The Cinematheque curators, on the other hand, treat film as if it were an art specimen. They evade trash, distrust conventional, popular narrative, and break out in hives at the mere mention of Steven Spielberg (unless it’s Godard putting him down). “[H]igh art can be just as fraudulent, evasive, and pandering towards its own constituencies as the lowest, most shameless Hollywood blockbuster,” wrote Howard Hampton in

Born in Flames, his lively book of essays on popular culture. Instead of providing audiences with an alternative to the worst in mass culture, the Cinematheque’s film curators have with this list made themselves an island onto themselves.

-- January 23/10

|

| Dariush Mehrjui's Pari |

I'm glad that I read J.D. Salinger’s

The Catcher in the Rye outside of any high school English class. Due to that fluke of good fortune, I was free to dip into Salinger’s tale of frustration without all the mythical baggage that comes with it. There's no question that his first novel had an indelibly profound impact on young readers (including very disturbed ones like Mark David Chapman). But the book’s influence also extended to movies as well (most notably in both

The Graduate and

Rushmore). But Salinger’s novel examined teenage misery with an acute eye. He didn’t enshrine his protagonist Holden Caulfield’s world view – rather he revealed that, in the world of ‘phonies,’ Holden was just as culpable as anyone he criticized.

The Graduate (1967) and

Rushmore (1998), in their blatant attempt to win over the outsider adolescent fringe of two very different generations, chose to pander to youthful narcissism instead. Both movies dubbed their rebel heroes as vulnerable, but they were largely self-righteous. They made dubious claims, too; since the adult world is automatically corrupt, by extension, it also corrupts its young.

Critic Alfred Kazin once wrote that Salinger chose the world of teenagers for his book to provide "a consciousness [among youths]…to speak for them and virtually to them, in a language that is peculiarly honest…with a vision of things that capture their most secret judgments of the world.” But the book questions that judgment by not allowing the reader to take refuge in Holden’s accusations. Rushmore was (as a friend of mine once wisely commented) like

The Catcher in the Rye - if written by Holden Caulfield. No director ever truly got the spirit of Salinger right – although Alan J. Pakula came pretty close in the rarely seen

The Sterile Cuckoo (1969), an adaptation of John Nichols 1965 novel about an eccentric teenager named “Pookie” Adams (Liza Minnelli) who experiences a painful coming-of-age during college life when she gets involved with a shy, young man (Wendell Burton).

|

| Wendell Burton and Liza Minnelli in The Sterile Cuckoo |

Although

The Catcher in the Rye is a wonderfully rich book that has earned its reputation as one of the great American novels about growing into adulthood, it isn’t my favourite Salinger. I reserve that place for

Franny and Zooey (1961), one of his many examinations of the eccentric Glass family (which include the short stories, “A Perfect Day for Bananafish” and “Raise High the Roofbeams, Carpenters”). The Glass family are a precocious clan torn apart by its sense of isolation and traumatized by the suicide of the oldest son, Seymour, their resident sage. The children, who once made radio appearances as child geniuses, create a unique bond among themselves. (Director Wes Anderson, who made

Rushmore, also tried to evoke

Franny and Zooey in his prosaic and whimsical

The Royal Tenenbaums.)

Franny and Zooey is a combination of two novellas. The first follows Franny Glass, a university student who is deeply troubled by the book, The Way of the Pilgrim, which is about achieving spiritual illumination through the chanting of a continuous prayer. In the second novella, she goes home to recover from a nervous breakdown brought on by her desperate need to understand the prayer. Her brother, Zooey, confronts her, helping Franny to face the existential burden being carried by their family as well as the wisdom that their elder brother Seymour left them. (Seymour’s suicide is covered in “A Perfect Day For Bananafish.”) The book is painfully funny. Frayed nerves get plucked by siblings who know each other so well that their banter resembles baggy-pants comedy routines conceived by Alan Watts. But

Franny and Zooey is also a rich and moving account about the claiming of spiritual solace – and its cost.

Salinger remained a recluse until his death last week, but he also famously denied anyone the right to do any adaptations of his work. But he likely never considered that some young Iranian film director named Dariush Mehrjui, who was spellbound by

Franny and Zooey, would make a movie adaptation in 1995 that was set in his own homeland. The movie,

Pari, was also about a young girl who is a student of literature. Like Franny, Pari (Niki Karimi) wrestles with her own spiritual crisis after reading the story of a 5th-century mystic who lost everything in a fire. That book is a legacy from Assad, Pari's older brother, who committed suicide by burning himself alive. Her youngest sibling Dadashy tries to dissuade her from following Assad's path and to resurrect her taste for life.

I was lucky to have caught

Pari while attending a series on Iranian cinema that same year. At first, not knowing that Pari was based on

Franny and Zooey, I was puzzled that I seemed to recognize the story. Within the first hour, however, I realized exactly what Mehrjui was doing – and what he produced was a remarkably intelligent and thoughtful adaptation of Salinger’s book, something he described as “a cultural exchange.” It’s a shame that Salinger didn’t extend the good will back to Mehrjui. Once his lawyers caught wind of

Pari, which was to be screened at the Lincoln Centre in 1998, Salinger had the film pulled from distribution.

Pari remains in a cultural abyss.

It’s sad that Salinger has now left us, but the good news might be that his estate may soon liberate film-makers to bring his work to the screen. Who knows? Maybe

Pari might even see the light of day again. That would be good news indeed. After all, Salinger's American inheritors so far have failed to capture the author's greatest gifts and insights in their own movies. It took an Iranian, coming to terms honestly with his own culture’s trappings and enlightenments, to finally get it right.

-- February 1/10

|

| Brad Pitt in Inglourious Basterds |

Although it's unlikely to win Best Picture at this year's Academy Awards (the best film on the list of nominations that I've seen is

The Hurt Locker),

Inglourious Basterds still comes as something of a happy surprise. Director Quentin Tarantino works from a movie-fed imagination, one that's completely soaked in a love of genre films – art movies, Asian action films, and exploitation pictures. But in his most celebrated works, like

Reservoir Dogs (1992) and

Pulp Fiction (1994), he made a fetish out of movie love. If Jean-Luc Godard had, according to author Paul Coates, once transformed movie audiences into film critics, Tarantino chose to turn his audience into pop culture junkies who savoured his insider movie references. In recent years, with the hubris of

Kill Bill Vol. 1 and

2, and more recently, the torpor of

Death Proof, Tarantino was pretty much swallowing his own tale. But

Inglourious Basterds, an alternate World War II action drama, shows Tarantino bringing his movie intoxication to bear on something more than just indulging a fetish. Without question, it’s his best film.

Inglourious Basterds is a pipe dream soaked in the aroma of old World War Two films. It's a fairy-tale account of the Second World War, where a Jewish guerrilla outfit led by a non-Jewish American southerner, Lt. Aldo Raine (Brad Pitt), wreaks havoc on the occupying Nazi army in France. As they send Adolph Hitler (Martin Wuttke) into fits of rage, Colonel Hans Landa (Christoph Waltz), known as “the Jew Hunter” (in a self-conscious style worthy of Columbo), also tracks down the Basterds. Although that’s the basic storyline, Inglourious Basterds sets up a number of narratives introduced by chapters (just as he did in Pulp Fiction). But this time the multiple stories deepen the underlying theme of the picture rather than call attention to their cleverness. As for the theme itself, film critic Shlomo Schwartzberg, writing in the

Canadian Jewish News, already put his finger on it. “

Inglourious Basterds evokes a ‘reality’ that so many Jews, understandably, wish had existed during World War Two,” Schwartzberg writes.”[It’s] a world in which Jews…could have taken charge of their own destiny without being beholden to non-Jews who, mostly, were indifferent to their fate.”

At its core, Schwartzberg’s point makes for a pretty potent subject, an alternate history that could inspire a justifiable blood lust, but (for once) Tarantino doesn’t use cathartic violence as a means to pander to the audience. Instead he wakes us from the illusions that those violent genre movies can create. He shrewdly mixes in real characters, like Hitler and Goebbels (Sylvester Goth), with fictional ones like Landa, German actress Bridget Von Hammersmark (Diane Kruger invoking Dietrich), who’s working with the Allies; and the Basterd Donny Donowitz (Eli Roth), who’s called “The Bear Jew” because of his abilities to club Nazis to death with his baseball bat. The strategy is to set up a dramatic shell-game with our cinematic memory. All through

Inglourious Basterds, Tarantino’s people don disguises, personas and allusions (mostly figures out of film and literature) only to have their masks ultimately stripped away.

|

| Christoph Waltz |

Tarantino works deftly with an international ensemble cast that speaks German, French, Italian and English. German actor Christoph Waltz, who deservedly won the Best Actor Prize in Cannes, is a frighteningly slippery figure, an unnerving portrait of the adaptable bureaucrat (by way of Klaus Barbie) who possesses an expedient morality. Waltz is clever enough to uncover the Nazi resistors but he doesn’t (except once) attack them; rather, he asks his prey leading questions that allows each individual to trip into his noose. (In these particular extended scenes, Tarantino has never written sharper dialogue that dramatically pays off.)

While I would have liked the Basterd members to be a little bit more defined, Brad Pitt gives Raine some nicely textured flourishes as a mountain man who doesn’t get turned into a hick. (Imagine an Appalachian Van Johnson playing Patton.) Melanie Laurent is also luminous as Shoshanna Dreyfus, a young Jewish refugee who survives her family’s slaughter at the hands of Landa. While living under an assumed name, she runs a small movie theatre and draws the amorous attention of a young German soldier Fredrick Zoller (Daniel Bruhl), who becomes a war hero after gunning down a number of Allied soldiers. To provide morale for the troops, Goebbels makes a movie about Zoller (with the soldier getting to portray himself). This marksman appeals to Goebbels to have the movie premiere at Shoshanna’s theatre in order to impress her. While Shoshanna agrees, it’s only so she can launch her own plot to avenge her parents. But unbeknown st to her, the Basterds are also cooking up a plan to trap the entire high command of the Nazi leadership who will also be in attendance. In those final scenes, which contain a few unexpected epiphanies,

Inglourious Basterds achieves a grandeur that is both spellbinding and unsettling.

Inglourious Basterds occasionally goes off the rails in tone (especially in some back-story inserts narrated by Samuel Jackson), but this is Tarantino’s most ambitiously fulfilling movie. Without losing any of his swagger, Quentin Tarantino has devised a story that uncorks his talent in a whole new way. By giving meaning and purpose to his abundant technique, he shows us what movie love is truly for.

-- February 2/10

“There is no music that you can say, ‘Oh, that’s Canadian – know what I mean? It’s North American music – different countries, but you hear the exact same music, from blues to cowboy. So rather than talking about Calgary or Montreal, we talked about places that we played in.”

--Robbie Robertson quoted in

Whispering Pines: The Northern Roots of American Music.

It’s been commonly held for years that Canadian musical performers only achieve their due recognition when they go south of the border. While that remains something of a simplification, there are still many examples to choose from – Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Gordon Lightfoot, just to name a few. Fortunately, in his recent book

Whispering Pines: The Northern Roots of American Music…From Hank Snow to The Band (ECW Press, 2009), author Jason Schneider develops a more substantial rendering of this phenomenon. By examining the Canadian songwriting tradition as a national narrative, he’s able to illustrate how our musical artists subtly permeate the American experience rather than seek out our neighbour’s validation. In a series of essays that chart the careers of Hank Snow, Wilf Carter, Ian & Sylvia and Leonard Cohen, Schneider (

Have Not Been the Same: The CanRock Renaissance) draws a delicate map of our cultural influence in popular music. He doesn’t so much examine how our identity as Canadians is felt in American music, but rather how American popular music has been enriched by our Canadian sensibilities.

Whispering Pines takes its name from the gorgeous Richard Manuel song on The Band’s second album, but it’s also an apt metaphor for how Canadian culture is often understated in its meaning. Where Americans, over time, developed a frontier mentality that brought forth both its riches and its arrogance, Canadians became humbled by the harsh landscape – we endure it and we also envelop ourselves in it. Schneider picks up on our need to explore (rather than conquer) with illustrations that include Hank Snow’s greatest song, “I’m Movin’ On,” Ian & Sylvia’s “Four Strong Winds,” Neil Young’s “Helpless,” Leonard Cohen’s “The Stranger Song” and Joni Mitchell’s “Urge For Going.” He ties the emotional reach of those songs to the mythic American folk and country traditions. All through the book, Schneider tells tales where American artists (like Bob Dylan and Ronnie Hawkins) become reoccurring figures who help Canadian performers seek homes abroad.

Schneider unfortunately doesn’t fully illuminate the meanings he finds in the songs of these Canadian artists. But he does have a storyteller’s gift of spinning fascinating yarns so that we can glean the deeper significance of their work for ourselves. Whispering Pines opens with The Band’s last concert (in their original line-up) in 1976, and then uncovers how the stage that evening was filled with Americans and Canadians who had all drunk from the deep well of North American roots music. He closes the book by contemplating their final failing as a group in creating a community out of their art. While this particular framing of Whispering Pines is ambitious, I wish Schneider had done more to create meaning out of The Band’s career (especially since their story runs like a leit motif throughout Whispering Pines). But as a study of the elusive nature of Canadian music, Schneider’s book is an invaluable study. It may not go far enough, yet in its own suggestive way, Whispering Pines reveals just how prominent our best artists and their music have become despite the way they operate in the shadows.

-- February 7/10

|

| Parker Posey in Broken English |

I can't think of another movie where a woman's desperate need for a relationship is dealt with both comically and painfully quite like Zoe Cassavetes’

Broken English. There is probably no other actress, either, better than Parker Posey who could delicately negotiate the shifting mood swings that such anxiety inspires.

Broken English, which had a very limited release in 2007, isn’t simply about the neurotic funk of being lonely. It’s about an attractive and intelligent woman whose ability to find a passionate and compatible relationship gets impaired by her rash decisions to mate. Cassavetes, who is the daughter of the late actor/director John Cassavetes, has definitely inherited her father’s love of actors but (thankfully) without imposing all his heavy-spirited psycho-dramatics on the picture.

Broken English comes closest to invoking the suffused moods of Sofia Coppola’s

Lost in Translation, or maybe Richard Linklater’s

Before Sunset (to which Cassavetes pays tribute here).

Posey plays Nora Wilder who works for a boutique hotel in the area of guest-services. It’s an apt job given that she is always looking after everyone else’s needs but her own. After setting up her best friend Audrey (Drea de Matteo, of

The Sopranos) with the man she ultimately marries, Nora wonders whether she will ever find Mr. Right for herself. Continually fueled by her anxiety and pressed on by her mom (Gena Rowlands, Cassavetes’ real mother) to find a man, Parker stumbles from one painful encounter to the next. But Cassavetes doesn’t belabour Nora’s misery and neither does Posey. Both women recognize that matters of the heart are as much absurdly comic as they are tragic.

One night at a party, Nora meets Julien (Melvil Poupaud), an attractive, but aggressively amorous Parisian, who initially alienates her. But his persistence is also tempered by a tenderness that she ultimately finds appealing. Poupaud portrays Julien as if he’s imagining himself being Jean-Paul Belmondo in Godard’s

Breathless. (Like Belmondo, he proudly wears a fedora on back of his head while continually nursing a cigarette.) As their romance tentatively unfolds, we see how Nora comes to realize that she has never allowed herself to recognize what she wants out of a relationship. Julien though knows immediately why he desires her, but his innate decency won’t allow him to dominate. He wants her to come around on her own terms.

Posey and Poupaud make the characters endlessly appealing. The couple are continually feeling out the emotional terrain that they uncover in each other – which, for Nora, is sometimes the utter fear of what she’s getting into. Eventually, Julien wants Nora to join him in Paris, but she can’t make the spontaneous decision to leave. Ultimately, with her friend Audrey in tow, Nora takes the leap to find him. But finding Julien turns out not to be as easy as desiring him.

While

Broken English doesn’t really represent any radical departure in moviemaking, the subtle shifts in dramatic texture help it transcend becoming merely a traditional genre piece. In the past, Parker Posey has portrayed a compelling cast of fascinating personalities in American independent pictures, but I don’t think she’s had a role that has provided for her as much range as she shows here. Zoe Cassavetes is obviously a director to watch. She has a compelling interest in letting a story find its own meaning rather than imposing meaning on it.

Broken English is about the ways that communication in romance can end up frayed and confused, but the film finds a fresh romantic spirit that mends the pieces.

-- February 8/10

|

| Death Defying Acts |

There are few directors who can capture the fragile nuances of human emotion quite like Gillian Armstrong. In

Mrs. Soffel (1984), she dipped into the deep well of longing that a repressed wife (Diane Keaton) developed for an incarcerated man (Mel Gibson). In

High Tide (1987), Armstrong elicited, with great subtlety and sadness, the unrequited yearnings a young daughter (Claudia Karvan) had for a mother (Judy Davis) who had abandoned her years earlier. In her adaptation of Louisa May Alcott’s

Little Women (1994), Armstrong went even farther than the previous adaptations of the classic novel. She captured, with both compassion and insight, the strong family bond of the March family while delicately illustrating the diverse desires and hopes of the growing sisters. In her best work, Armstrong’s great gift is for working between (and within) the lines of the story.

Her latest film,

Death Defying Acts (2008), is also about emotional bonds – between mother and daughter; men and women – only it’s not nearly as cohesive, or as satisfyingly worked out. Yet there is still something shimmering about this picture, something ghostly that helps compensate for some of the movie’s dead spots. Part of the picture’s alchemy has to do with the fact that the story is about magic – both what is real and what is fake. Magician Harry Houdini (Guy Pearce) is visiting Edinburgh, Scotland in 1926 to offer $10,000 to anyone who can help him contact his dead mother and reveal to him her last words. Thirteen years after her death, Houdini is still possessed by the fact that he wasn’t at her side when she passed away. Meanwhile, two con artists, Mary McGarvie (Catherine Zeta-Jones) and her daughter Benji (Saoirse Ronan), have been desperately making their living fleecing customers with a bogus psychic show. (While Mary performs the tricks, Benji sneakily gathers information from the audience needed to help her mother pull off the scam.) When Houdini comes to town, they immediately zero in on the possibility of winning the money. What ensues is a romantic entanglement between Mary and Houdini that’s interrupted by the knowledge that Benji may possess magical gifts that go far beyond scamming.

Part of the failing of

Death Defying Acts is the lack of mystery in Catherine Zeta-Jones. Since her lively appearance years ago in

The Mask of Zorro (1998), she has been little more than a beautiful blank on the screen. Her earnest approach to her role here makes her seem somewhat indistinct and bland – not believable qualities for a scam artist. Her romantic encounter with Houdini, while intitially part of the seductive rouse, also simplifies the story’s strengths by overshadowing the film’s core dynamic of her relationship with her daughter. Saoirse Ronan, on the other hand, has magic coming out of her fingertips. She equals her startling work as the young precocious Briony Tallis in

Atonement (2008). Ronan plays Benji with a mischievous zeal, like a Dickens' gamine, a ploy that masks her adolescent frustrations towards her mother. This young actress performs with such imagination and lyricism that you wish Carol Reed had lived to direct her. Pearce’s Houdini is somewhat stylized, but he doesn’t turn the magician into a cartoon. Unlike the horribly mannered work Pearce has done since his satisfying turn as the straight-arrow cop in

L.A. Confidential (1997), Pearce does some nimble work here. He reveals Houdini to be a man who believes that performing magic can cheat the reality of death - except the death that continues to haunt him.

Death Defying Acts gets a lot of its facts wrong (for example, Houdini didn’t die in Montreal, it was in Detroit), but Armstrong’s film is strongest when she shows us how the spirit of magic is sometimes inseparable from human yearning. The cinematography by Haris Zambarloukos is also so beautifully textured so that the characters appear like spectral figures laminated on the screen. The script, by Tony Grison and Brian Ward, might not provide Gillian Armstrong with a full deck, but in

Death Defying Moments she still knows how to play the hand that’s dealt her.

-- February 14/10

Although The Beatles got all the credit for spearheading the British Invasion into America in 1964, the first rock band to literally tour the United States was The Dave Clark Five. Driven by a heavy sound that

Time Magazine compared to an air hammer, The Dave Clark Five sold in excess of 50 million records and appeared a record 12 times on The Ed Sullivan Show. So, given these accomplishments, why didn't they reign supreme? First of all, musically the band was nowhere near as talented as the Fab Four. Their songs ("Glad All Over," "Bits and Pieces") were driven by a pounding Big Beat, but their timbre ultimately grew deeply monotonous. They were also a colourless group, indistinct in comparison to the madcap Beatles. "Sure they were crude and of course they weren't even a bit hip, but in their churning crassness there was a shout of joy and a sense of fun," wrote critic Lester Bangs in appreciation. Given that their greatest appeal was in that spirit of simple fun, it was a huge shock to discover that in their first movie,

Having a Wild Weekend (1965), they would end up providing such depth. To borrow film critic Andrew Sarris's comparison:

Having a Wild Weekend is to

A Hard Day's Night (1964) what Sarris says Orson Welles'

Citizen Kane (1941) is to

The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), an uneven, but emotionally richer experience than the former.

Having a Wild Weekend, which was more aptly titled

Catch Us If You Can in the United Kingdom, is a story about the cost of being a tool of mindless commercialism. It's about how one defines success, and whether or not it does bring complete happiness, or even satisfaction. Having a Wild Weekend is not about the alienation of youth (always a popular theme), it's about disenfranchisement. The movie examines the price of utopian dreams, how they are defined, or if they can be sustained if they are ever found.

A Hard Day's Night celebrated The Beatles' fame, and it did so with great affection.

Having a Wild Weekend asks more unfriendly questions about what fame really has to offer. Directed by John Boorman, his first dramatic feature, and written by playwright Peter Nicols (

A Day in the Life of Joe Egg),

Having a Wild Weekend took a number of risks that

A Hard Day's Night chose to avoid.

|

| Dave Clark Five |

A Hard Day's Night has The Beatles playing themselves in a film that both mythologizes and celebrates their music. In

Having a Wild Weekend, The Dave Clark Five don't play themselves. The movie isn't even about how a rock band achieves fortune. The Dave Clark Five are playing stuntmen working on a TV commercial being produced for an advertising company selling meat. Steve (Dave Clark) is a model who is unhappy with his life. He works with Dinah (Barbara Ferris), the "Butcher Girl" in the company billboard ads. One day, they've had enough of the vapid commercialism, of being turned into products of the advertising firm. In an act of desperate rebellion, they impulsively leave London to explore the English countryside. Their valiant hope is to find a better and more meaningful life, while the advertising company spends the movie trying to hunt them down. What they discover on their journey is more people desperately trying to survive their shattered dreams. They first encounter some squatting hippies on Salisbury Plain in a gutted house smoking grass, but the squatters are seeking something harder - heroin. Although it's 1965, the commune members suggest the dissipated and drugged wanderers of the late sixties, those who would become fodder for the crazed visions of Charles Manson.

They later meet an unhappily married couple (played with bitter perfection by Yootha Joyce and Robin Bailey) who are collectors of arcane objects that help them cling to the past in their extravagant estate. But their antique goods can't heal the angry emotions that continually tear the couple apart. The thrust of Steve and Dinah's journey, throughout the movie, is to get to an island off the mainland in Devon where they can find sanctuary from the corrupted world around them. But the island is as much a phantom refuge as Moscow was for Chekhov's

Three Sisters.

It's not hard to understand why

Having a Wild Weekend failed to score with the fans of The Dave Clark Five. (The picture bombed.) Instead of playing off of the band's pop appeal, or celebrate the spirit of liberation in the air, John Boorman speculates about what freedom Steve and Dinah could possibly find outside of their own milieu. In many ways,

Having a Wild Weekend was a sober meditation on a period that people wished to define as idyllic. Ironically, while the Dave Clark Five would soon drift into relative obscurity next to The Beatles; by 1966, The Beatles themselves would begin to live out aspects of what was so presciently unveiled in

Having a Wild Weekend.

-- February 16/10

"You can't have progress without deviation from the norm," composer Frank Zappa once wrote. Glancing back on the history of popular music, it shouldn't come as any surprise that it contains a long list of deviators. Out of their time, and breaking and remaking all the rules, these innovators dauntlessly set out to change history. While gleefully altering our perceptions of the world, these artists deviate most from the norms we take for granted. American outsiders are the most compelling to watch since they tend to transform themselves along with their work.

In 1925, Louis Armstrong, already a major jazz performer, decided to turn the music on its ear with a series of masterful recordings with the Hot Five and Seven. By reconstructing jazz into a soloist's art form, Armstrong was conveying a secret to all Americans: It's more exciting to stand out from the crowd than it is to join it. A few decades later, a young saxophone player from Kansas City named Charlie Parker decided to answer Armstrong's invitation by breaking the rules of standard harmony. While riffing at lightning speed, Parker ingeniously played within the chords themselves. Soon after, a young truck driver named Elvis Presley walked into Sun Studios in Memphis and made the cocky claim that he sounded like nobody else. Within a few years, he effortlessly altered the face of American music.

On the other hand,there is a whole other breed of outsider, whose talents aren't about innovation, self-transformation or changing the face of the culture. Quite the contrary: these artists live in a world shaped by their own peculiarities, and their music eagerly expresses those oddities. There is no danger that these visionary cranks will set the world aflame, but a compelling world is still tucked away within their music, a world that sets them apart, too, from the bland and homogenous conventions that mark the path to pop stardom. Irwin Chusid, a music historian and the host of WFMU's "Incorrect Music Hour," first termed this mutant strain "outsider music," and he wrote about it in a fascinating book called

Songs in the Key of Z (2000).

Focusing on such unusual talents as Daniel Johnston, Joe Meek, Jandek and Wesley Willis, Chusid defined outsider music as "crackpot and visionary music, where all trails lead essentially to one place: "over the edge." In the music of Jandek, for example, a reclusive young Texan who has released over 30 homemade LPs, you hear a distinctly shattered performer. In a voice that sounds like Neil Young after he's been shot full of holes, Jandek seems to be reading suicide notes rather than singing songs. Jack Mudurian is a resident in a nursing home in Boston who professes to "know as many songs as Frank Sinatra did" - actually, he knows a lot more. To prove it, Murdurian once dared a hospital staff member to get his cassette recorder, then offered up an impromptu forty-five minute performance. When he was finished, Mudurian had blurted out a completely improvised and unedited 129-song medley that was gathered on an album called

Downloading the Repertoire.

In Freemont, New Hampshire, a trio of sisters, Dorthy, Helen and Betty Wiggins, went into a local studio in 1969 to record an album called

Philosophy of the World. Calling themselves The Shaggs (because of their long thick locks), their music couldn't be more disharmonious, with missed beats, shredded chords and innocent, almost naive lyrics. One of their songs, "My Pal Foot Foot," was about their pet cat. Where some dismissed it as one of the worst albums ever made, others insisted

Philosophy of the World was one of the most original and indigenous of American records. (Of that, there's no question.)

Philosophy of the World continues to cause debate some forty years after its release;

Rolling Stone called it one of the most influential alternative releases ever made. Frank Zappa once tried to land The Shaggs as an opening act. Bonnie Raitt referred to them affectionately as castaways on their own musical island. What Chusid's book, and its CD soundtrack attests, is that the grain of outsider temperament, wherein you set the terms of your own acceptance, inspires this motley crew to make their own kind of music. With their faint hope of chart success, the outsider's daunting task still remains a compelling one. While playing out their part as Raitt's castaways, they remain a weird distillation of pure American ambition.

-- February 17/10

|

| Mark Ruffalo and Leonardo DiCaprio in Shutter Island |

Martin Scorsese’s

Shutter Island is less an adaptation of author Dennis Lehane’s mystery thriller than it is a virtual funhouse of the director’s favourite film noir tropes – only there’s no fun in it. As he did in his ridiculous re-make of

Cape Fear (1991), Scorsese gets so absorbed invoking the work of various film stylists - including Jacques Tourneur's

I Walked With a Zombie (1943), Vincente Minnelli’s

The Cobweb (1955), Don Siegel’s

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), Alfred Hitchcock’s

Vertigo (1958) and Sam Fuller’s

Shock Corridor (1963) - that he can’t find a style of his own to take us inside the drama. Working from a dense but convoluted script (by Laeta Kalogridis),

Shutter Island is a cluttered labyrinth that begins as an ingenious detective story but slowly shifts into a psychological character study. However, Scorsese gets so jazzed on creating a surreal atmosphere, aided by the atonal sounds of Ligeti, Penderecki and John Adams, that he clouds the clarity of the story. If it wasn’t for the good work by many of the performers, desperately breathing life into their stock roles, the picture would sink under the weight of the director’s B-movie fetishes.

Set in 1954,

Shutter Island tells the story of two newly partnered U.S. marshals, Teddy Daniels (Leonardo DiCaprio) and Chuck Aule (Mark Ruffalo), who take a ferry across the stormy waters of Boston Harbour to the Ashecliffe Asylum on Shutter Island. They've been assigned to find Rachel Solando, a female inmate who vanished from her cell without a trace. (Rachel was sent to the Island after murdering her three children and arranging them around the dinner table for her husband to find.) On this remote estate, they’re introduced to the chief physician, Dr. Cawley (Ben Kingsley), and his cohort, Dr. Naehring (Max von Sydow), who aid them in their investigation. But from the moment they arrive, while a hurricane brews menacingly outside, the disappearance doesn't add up and stormy memories are starting to cloud Teddy Daniels’ judgment. Daniels begins to suffer from blinding migraines brought on by visions of the trauma he experienced liberating Dachau with Allied Forces and of the later death of his young wife (Michelle Williams). Before long, Daniels suspects that the asylum may be housing sinister experiments brought on by the Cold War paranoia of the Fifties in which he himself may soon become a victim.

Although

Shutter Island is full of portentous imagery, the dread it evokes is largely mechanical. In his early work, like

Mean Streets (1973) and

Taxi Driver (1976), Scorsese successfully dramatized psychological turmoil by going deep inside his protagonists’ unrest so that we fully experienced their distorted world view. In

Shutter Island, Scorsese stays safely on the outside and portrays Daniels’ hall-of-mirrors world more like a series of abstractions. (His haunting hallucinations, meticulously shot by Robert Richardson, are as literally and dramatically inert as the ones in Stanley Kubrick’s

The Shining.) If David Lynch and Neil Jordan find realism in the dreamscape of surrealism, Scorsese’s strengths (which he abandons here) are in uncovering surreal states in dramatic realism.

Shutter Island might be about how we invent comfortable worlds to live in as a defense from memories and impulses too painful and too violent to acknowledge. But that’s also Scorsese’s dilemma here as a director: he creates a comfortable world out of effects from film history to avoid delving too deeply into the dramatic conflicts of his characters. As a director who once wrestled with violence, at times unflinchingly, Martin Scorsese is now taking refuge in formal technique.

Despite the deficiencies of

Shutter Island, the actors keep grounding the story. Leonardo DiCaprio fits snugly into the broad fedora and long coat of past noirs, but he also manages – especially late in the picture – to create a searing, tragic portrait that cuts through the morass of the plot. Mark Ruffalo brings a calm, quiet presence to his supporting role that transcends the usual detective story clichés. Emily Mortimer has a beauty of a cameo, too, as an inmate whose burst of anger sends shock waves through the lovely contours of her face; as does Patricia Clarkson, playing a former psychiatrist, whose calm paranoia tells Daniels something about the truth behind the possible horrors he’s beginning to unravel. Ben Kingsley and Max Von Sydow could both have floated off into hambone heaven, but unlike Jack Nicholson in Scorsese’s last movie,

The Departed, they give measured and low-key performances.

A lot has been made over the years about Scorsese’s reverence for the movie past which is why many critics continue to call him a master. And in some of his best work, where he uncovered and revitalized a number of genre conventions, his unbridled love of film did make him a great artist. But in his last few movies – from

Gangs of New York (2002) to

Shutter Island – his passion has been replaced by an impersonal craftsmanship. He still knows how to make a movie but some of us are now left wondering why he’s making it. You could say that Martin Scorsese is currently on his own Shutter Island, a movie theme park, playing out his role as master and lost in the storm.

-- February 19/10

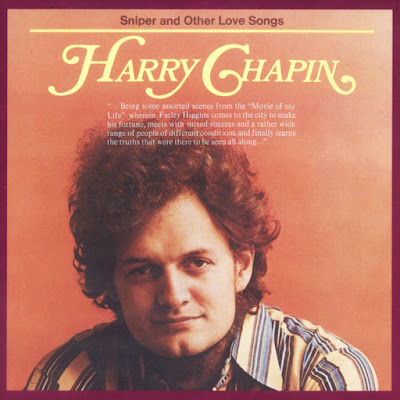

My good friend Adam Nayman and I were once discussing people who you always expect to miss the point. But we agreed that sometimes - maybe just once in their life - they got it right. That lead me to think about the late singer/songwriter Harry Chapin. Chapin was a composer of short-story songs and they often centered on society’s “little people.” Whether it was the poor sap wistfully remembering a lost love affair in “Taxi,” or the DJ who’s time has faded in “WOLD,” or (worst of all) the dad who doesn’t take time to pay attention to his growing son in “Cats in the Cradle,” Chapin was pop music’s Paddy Chayefsky. All everyone needed was love and attention and the world would be fine.

Right.

But one of his early songs, one that rarely gets played on the radio, or even recognized as a Harry Chapin song, is a track called “Sniper.” The title tune from his second album in 1972, “Sniper” wasn’t about the benign, fictional “little” Americans that populated his usual repertoire. This particular song was about a real killer, the American sniper Charles Whitman. Over forty years ago, Whitman stood in a tower at the University of Texas in Austin and shot and killed 14 people and wounded 32 others in a shooting spree on the campus. (The massacre happened shortly after he had murdered both his wife and mother.)

Chapin takes the same approach to this song as he did with many others (if only Whitman had been loved by his mother, he would have been sane). But his neo-Freudian interpretation gets overturned by the sheer force in his singing, in the way the character of Charles Whitman keeps taking over the song and claiming it back from any easy summing up of his life. Chapin’s gift was his ability to get inside the characters in his compositions – whatever one thought of his songs. He spoke in the voice of the person in the tune and made you see the world through their eyes. But in “Sniper,” Chapin got more than he bargained for. On the album, “Sniper” is overproduced with effects, but Chapin still manages to rise above the aural clatter. All through the song’s over nine-minute length, as he describes Whitman’s moments climbing the tower, his glee at firing the gun, the stunned reports of news reporters and witnesses, Chapin is breathlessly swept away by the rage he’s unleashed in the character. Music critic Sean T. Collins deftly touched on some of the sheer intensity of “Sniper”:

“It’s a[n] … unusual topic for the man behind ‘Sunday Morning Sunshine.’ But the earnestness with which Chapin imbued his folksy love songs serves this macabre subject well. Chapin is no more able to hide behind irony or ambiguity here than he is in his more romantic work, forcing the audience to come directly to terms with the horror of the sniper attack, and the tortured character of the sniper himself. Over the course of the song's 9 minutes and 55 seconds, Chapin and his dexterous backup band wind, segue, and careen from tempo to tempo, key to key, style to style. Here they're conveying the quiet of the early morning campus, while the protagonist walks toward the clock tower. Here they're mimicking the buzzing teletype and breaking-news noise of the special reports updating viewers and listeners on the shootings. Here they're deploying simple, sparse staccato to simulate the slaying of yet another too-curious bystander. Here they're using cello and chorus to depict the mournful, vengeful mother fixation of the title character. Here they're building toward the climactic showdown between sniper and police, replete with gas-dropping helicopters and ‘final fusillades.’ And here [they crescendo] to a ‘Day in the Life’-style nihilist's triumph. A band trained for simplicity, their discipline serves them extraordinarily well, tempering excess and making every musical metaphor.”

Of course, the metaphors are obvious and no more open-ended than the ones in “Cats in the Cradle,” but Chapin’s performance overturns his pat conclusions. But if the album version is overproduced, the live performance he gave of the song in 1975 for PBS’s

Soundstage, remedies the problem. With no trick sound-effects, “Sniper” gets stripped down to just what his ensemble can re-create on stage. Chapin is almost maniacal here, as if determined to take back control of the song. But Whitman possesses him to the point that you can feel Chapin's band backing away. The audience applauds at the end but likely with relief. I had just come back from school that evening and one of my roommates just happened to be watching

Soundstage. As I put my bag down, I stood staring at the TV with an eerie sense of not knowing how far Chapin would go. As the song continued to sing him, I sensed that after that performance, I’d never hear anything of that power from the man again.

And I didn’t.

-- February 25/10

|

| Charles Ives |

“The quest for identity runs through American music like a leitmotif,” writes music critic Veronica Slater. “Long before musical nationalism became an issue in Europe, native-born composers in the New World were trying to speak with a voice recognizably theirs and theirs alone.” Americans, according to Slater, rebelled against the rules in both politics and music for good reason. They were after an indigenous art rooted in their own experience of the new land, not what they inherited from the Old World. The map of that rebellion and quest is aptly provided in Frank Rossiter’s rare and illuminating study of American composer Charles Ives in his book

Charles Ives & His America (1975).

Born in 1874, in Danbury Connecticut, Ives had little patience for what Slater would call the “elegancies of late-18th-century music.” In the America he envisioned, European decorum had no place to park. According to Rossiter, Charles Ives was born into an America where the chasm between the “cultivating” arts and the “popular” arts was long and wide. Composers in the United States at that time were steeped in the European romantic sensibility that emphasized “the sublime and spiritually exalted in the arts,” as Rossiter puts it. This meant the cultural arbiters of taste in America wouldn’t draw their inspiration from their new roots, but from the Old World values of Handel, Haydn and Beethoven. By the time Ives arrived, American composers of classical music were either trained in European schools or by European teachers in America. In

Charles Ives & His America, Rossiter explores how, before Ives, America was cut off from “the popular culture of their own country” because they lacked a tradition of art music comparable to Europe. When Charles Ives began composing, he found the American voice in its folk hymns, marching band music and its patriotic tunes. He radically transformed this popular musical vernacular into mutating soundscapes, as in his boldly dissonant “4th of July,” that used collage and asymmetrical rhythms.

Rossiter also clearly illustrates why Ives’ rebellion against European gentility took on an ebulliently harsh tone. (He called Chopin “soft…with a skirt on;” Mozart was “effeminate.) Like Ernest Hemmingway, Ives defined American art in the narrow terms of masculine assertion. But that was hardly accidental. Film editor and scholar Paul Seydor once asserted in his fascinating study of film director Sam Peckinpah (

Peckinpah: The Western Films) that the “artistic revolt in America has…always been masculine in character, with its emphasis on hardness, clarity, simplicity, boldness, difficulty, exploration, independence and rebelliousness.” Since women were excluded from professional and prestigious positions in business, those in the upper classes turned to music for leisure and a livelihood. They embraced the cultivated music of Europe. Early in the 20th century, women made up the majority of audiences at operas and concerts, and the majority of music students, too, and even wrote most of what constituted music criticism. “Women became dominant in cultivated-tradition music because the European system of selecting out and educating a body of males to carry on artistic traditions had never caught hold in America,” Rossiter writes.“And as women’s dominance grew," he explains, "American men retreated from classical music as a threat to their masculinity.” In his work, including

Three Places in New England and the

Concord Sonata, Ives stripped cultivated music of its genteel attributes as he were unmasking the true American character – and, of course, freeing the country from its colonial past.

That Ives turned to music, though, created a profound conflict. “When other boys…were out driving grocery carts, or doing chores, or playing ball, I felt all wrong [staying] in and [playing] piano,” he wrote in his memoir

Memos. If women had represented gentility, they still cultivated American arts and Ives’s revolt is partly an attack on the very foundations that created him. “[R]ebelling against the official culture an artist is necessarily going to find himself betraying or at least suppressing some of his deepest leanings towards art and expression,” continued Seydor about Peckinpah, an artist who certainly shared some of the same conflicts and ambition of Charles Ives.

However, Ives’s ruggedly masculine assertions didn’t grow out of misogyny. He took on gentility, not women. His radically bold work further illustrates that elegance is not part of the American character because the land, and the foundations on which the country was founded, are anything but harmonious and sweet. Ives believed that ruggedness was the only true response to the spiritual legacy of being an American. Ralph Waldo Emerson once wrote in his

American Scholar (1837) that “our day of independence, our long apprenticeship to the learning of other lands, draws to a close. We have listened to long to the courtly muses of Europe…We will walk on our own feet; we will work with our own hands; we will speak our own minds.” Even if music would be one of the last American art forms to walk on its own feet, Charles Ives certainly heard the call to speak his own mind and gave voice to the living speech of the culturally disinherited.

-- March 3/10

Every year at the Oscars, people concentrate primarily on the Best Picture and Acting categories. But I always like focusing on the Best Documentary Feature section because the people who make them – good and bad pictures alike – have something more at stake than the box office results. This is often why their speeches are either the most moving (or the most proselytizing). Of the five nominated films this year, I’ve only seen three of them.

It’s often been said that you are what you eat, but after seeing Robert Kenner’s incendiary documentary

Food Inc.– which examines how the fast food industry radically transformed food production in North America into a stomach-churning enterprise — you just might want to redefine those terms. While

Food Inc. is thankfully not alarmist in tone, the facts it uncovers are nevertheless alarming. Using as his guides author Eric Schlosser (

Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal) and UC Berkeley School of Journalism Professor Michael Pollan (

The Omnivore’s Delight), Kenner examines how the mass-produced food we now consume is not only lacking in proper nutrients; it may also contain potentially harmful bacteria.

|

| Food Inc. |

The story begins with McDonalds, who set the template for cheap assembly-line food production, then shows how American farms have now become equally uniform – and at the horrible price of creating unhealthy working conditions for both workers and livestock. We may end up spending less for the food, but we pay dearly for it with increasing cases of diabetes, obesity and E. coli outbreaks. It’s unfortunate, though, that because many of the corporate industrial heads like Monsanto refused to be interviewed for the film,

Food Inc. ends up lacking a larger dimension than its agit-prop intent. (Thankfully, due to the co-operation of Walmart, they come across far more ecologically minded than usually assumed.) Like

An Inconvenient Truth,

Food Inc. lays out its argument clearly, but it’s only one side of the story. To be a truly great documentary,

Food Inc. needs a few other conflicting morsels of thought to chew on.

On the other hand,

The Cove, a documentary that exposes the slaughter of dolphins in the Japanese fishing town of Taiji, has nothing going for it but its agit-prop intentions. It clobbers the audience so intensely that you may experience caution about raising any objections to the film. It’s as if by questioning the movie’s aesthetic you’ll be found guilty of handing out the spears and harpoons to the killers. But that’s exactly the paradigm

The Cove sets up – an Us vs Them dynamic that I believe weakens the story. To quickly transform the movie audience into instant activists (just add melodrama and stir),

The Cove by-passes a contemplative investigation of the hunt and instead uses nakedly visceral techniques to outrage its viewers.

|

| The Cove |

Director Louie Psihoyos (who is a former National Geographic photographer) and animal rights activist Ric O’Barry (a former dolphin trainer) are appalled by the cruelty taking place in the cove (where dolphins are rounded up and either killed for food, or sent to a living death in marine parks), but due to government and fishing industry collusion, they can’t prove it. (Apparently, close to 23,000 dolphins are driven into the cove each year.) So Psihoyos and O’Barry decide to organize a team with thermal cameras and night-vision goggles to slip by the secured location and (with hidden cameras) capture the hunt in order to expose the fishermen. Since

The Cove borrows the methods of a thriller it has a certain dramatic kick when we watch the team organize their battle plan like a commando team. And the footage they get is as horrifying as you can imagine. But given our anthropomorphic identification with dolphins, it seems crudely manipulative to use that footage to stir those sentiments in the viewer while simultaneously indicting the hunters. (I somehow doubt that footage of the group massacring electric eels would have the same impact on the movie audience.)

As well as directing the film, Louie Psihoyos is also the co-founder of the Ocean Preservation Society. So

The Cove has an ecological agenda that it proudly wears on its sleeve. Now I’m not suggesting that because of this the movie traffics in the bad faith that Michael Moore’s pictures do. What I’m saying is that the film is trying to be a recruitment poster as well as a criminal indictment – and the two don’t mix very comfortably.

The Cove is powerful and effective and it outrages and disgusts. But it also gets the audience cheering when the bad guys are outted. The one thing

The Cove doesn’t do is encourage you to think.

The Most Dangerous Man in America: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers not only encourages you to think, the picture’s subject – the ethics of political activism – stands in sharp contrast to what passes for activism today. When Ellsberg leaked the

Pentagon Papers in 1971, he wasn’t just staging guerrilla theatre (as were Abbie Hoffman and the Yippies), he set out to show how American foreign policy towards Southeast Asia and Vietnam was built on a series of lies. Ellsberg had originally been part of what became the strategy behind the Vietnam War, as both an analyst for the Defense Department and a marine, who first held that if the country went communist, it would be part of a domino theory that would ultimately plunge the region into Stalinist totalitarianism. While it turned out that the country eventually did plunge into Stalinist oppression after the Americans left in 1975, with more than one million Vietnamese fleeing by boat (half of whom, ironically, would land in the U.S.), Ellsberg’s change of heart towards the war was justified. He spoke out because a series of Presidents, from Truman to Nixon, had cooked the facts to support the need for U.S. involvement. (His first day working for Defense Secretary Robert McNamara was the same day of the Gulf of Tonkin incident when North Vietnamese ships were believed to have fired torpedoes at U.S. boats. Although the attack was known to be false, President Johnson decided to use this episode to expand the war.)

The Pentagon Papers, which were released to

The New York Times and other publications, were essentially the secret history of the Vietnam War. Ellsberg went public – risking prison and career – with these documents on the principle that supporting fabrications and brutal dictatorships in order to fight communism was immoral.

|

| The Most Dangerous Man in America |

The Most Dangerous Man in America (the phrase Henry Kissinger used to describe Ellsberg) is told largely from Daniel Ellsberg’s point of view, along with supporting interviews with the late Howard Zinn and self-damning comments from Richard Nixon’s famous secret tapes, but the film-makers Judith Ehrlich and Rick Goldsmith have also fashioned another crusade. Besides being a compelling historical saga, it is also a personal story of how a man of conscience was motivated to act on the principle of positive rebellion and how those actions changed him from the man that he once was. It’s a little bracing to recall a time when mainstream journalists were after more than just the careerist desire to be hip and consumer friendly. No doubt that careers got made doing groundbreaking stories like

The Pentagon Papers, but the risks were also more dangerous. (

The Pentagon Papers inspired Nixon to set up his secret government and led to his downfall with Watergate.) Of course, it would be too easy and too simple today to equate Vietnam with the war in Iraq and how pack journalism (like cliques in high school) prefers to go with the flow, but

The Most Dangerous Man in America gives one pause over what was gained by Ellsberg’s actions and what’s been lost since.

-- March 7/10

|

| Chow Yun-Fat & Jonathan Ryhs-Meyers in The Children of Huang Shi |

It’s bad enough when good movies get dumped on DVD without first getting a theatrical release. But it’s even worse when the DVD release also gets ignored. (DVD reviewers often miss these films because they either don’t know they exist, or their editors don’t care enough to have

anyone know they exist.) Whatever the reason,

The Children of Huang Shi certainly deserves a better fate than its remaindered status in the Blockbuster cut-out bin.

Based on the true story of George Hogg (Jonathan Ryhs-Meyers), a British photo journalist during the early days of the Japanese occupation of China in 1938,

The Children of Huang Shi is about how an opportunistic journalist turns into a true humanitarian. After pretending to be a Red Cross aid worker (in order to sneak into Nanjing to get a big story), Hogg confronts horrific Japanese atrocities and gets captured after photographing them. He gets rescued by a Communist resistance fighter (Chow Yun-Fat) who arranges to have him sent to an orphanage in Huanghshi to assist Lee Pearson (Radha Mitchell), the American nurse who is running it. While he’s initially reluctant to care for the 60 orphan boys living there (and they are alternately not too pleased to have him caring for them), he gains their respect by giving them the kind of attention they’d long given up hope of ever getting again.

Depicting a photo journalist who comes to terms with his role in life is not new to director Roger Spottiswoode, who earlier in his career made the satisfying produced-and-abandoned political drama

Under Fire (1984). In that film, a contemporary story set in Nicaragua, a photo journalist (Nick Nolte) transforms himself from an objective observer into a committed activist while simultaneously examining the consequences of his actions.

The Children of Huang Shi, however, doesn’t contain the same layered ironies that are woven into

Under Fire. The dramatic arc of the picture is much more conventional. But the movie remains a beautifully directed piece of work. In particular, the period details, captured by cinematographer Zhào Xiaodīng (who also shot the luminous

House of Flying Daggers), are done in deep pastel colours that enrich the narrative's fermenting intensity.

While Jonathan Rhys-Meyers has often been to acting what Rufus Wainwright is to singing (making every gesture a dramatic affectation), he does his least ostentatious performing on the screen yet. Radha Mitchell’s work as the nurse begins rather stiffly but she gradually comes to reveal how the relentless horror eats away at the idealistic zeal that once fueled this woman's work. Chow Yun-Fat has a small part but he demonstrates an abundance of audience rapport. (His smile is as wide as the screen itself when he detonates buildings he knows will annoy the Japanese invaders.) Michelle Yeoh has an even tinier role as a woman who smuggles drugs to assist the children (and to aid a little habit the nurse has been nursing), yet she's striking in every scene carrying the weight of melancholy in her beautifully expressive face. There are a number of Chinese actors in the roles of the children and every one etches vivid portraits of how young promising lives can get reduced to basic survival.

The Children of Huang Shi is the kind of movie that is profoundly moving without becoming self-consciously inspirational.

-- March 13/10

|

| Matt Damon in Green Zone |

In his sane and sobering book

The Assassins’ Gate: America in Iraq (2005), The

New Yorker’s political correspondent George Packer opened up one’s perspective on the Bush Administration’s argument for invading Iraq on the danger of their using weapons of mass destruction:

“[Bush’s] 'axis of evil’ speech, coming just weeks after the fall of the Taliban in Afghanistan, signaled the next stage in the war on terrorism and the basis for further action. The speech dramatically expanded the theatre of war, but it also did so on relatively narrow grounds. As [Paul] Wolfowitz told an interviewer after the fall of Baghdad, WMD was the least common denominator: ‘The truth is that reasons that have a lot to do with the U.S. government bureaucracy, we settled on the one issue that everyone could agree on, which was weapons of mass destruction.’ Wolfowitz suggested that he himself had bigger ideas – a realignment of American power and influence in the Middle East, away from theocratic Saudi Arabia (home to so many of the 9/11 hijackers), and toward a democratic Iraq, as the beginning of an effort to cleanse the whole region of murderous regimes and ideologues…Resting on a complex and abstract theory, it would also have been much harder to sell to the public.”

It’s a shame that Paul Greengrass in his new film

Green Zone also resists such complexity because the movie turns out to be as single-minded in its approach to the Iraq War as the Bush Administration’s. Based on

The Washington Post’s correspondent Rajiv Chandrasekaran’s book

Imperial Life in the Emerald City (2006), which documented the tumult in the aftermath of the removal of Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein,

Green Zone sets out to expose the false pretenses for the coalition’s actions on the grounds that Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction were never found. Greengrass brought a nuanced understanding of political conflict in his searing study of the Irish Troubles in

Bloody Sunday (2002), and created a chilling atmosphere of realism in

United 93 (2006) that chronicled events aboard United Airlines Flight 93, which was hijacked during the September 11 attacks, but he fails in

Green Zone to illuminate the cause of the hubris back in 2003.

Green Zone instead becomes an obtuse, routine conspiracy thriller that gets lost in the shadows.

For about the first half-hour, Greengrass raises our expectations that

Green Zone will be about a lot more than just missing WMD. It begins with the horrific fall of Baghdad in a rain of bombs – the ‘shock and awe’ - which Greengrass powerfully recreates like a tableau of fiery furnaces. In the aftermath, Roy Miller (Matt Damon), a warrant officer, is assigned to find Iraq’s mother lode based on military intelligence from a mysterious source. But his crew keeps coming up empty, so Miller questions the brass about the competency of their information. He gets no satisfaction from his superiors; however, he draws the attention of CIA agent Martin Brown (Brendan Gleeson) who is becoming equally skeptical of the mission. While investigating another site, Miller gets approached by an Iraqi who calls himself "Freddie" (Khalid Abdalla). He tells Miller that he saw General Al-Rawi (Igal Naor), an expert in Iraqi WMD and possible source, at a meeting in a nearby house. Believing that Al-Rawi holds the key to the mystery of the missing WMD, Miller goes AWOL to capture the General. Although Al-Rawi escapes, one of his henchmen is captured with a book that lists his safe houses. When news of the book reaches American administrator Clark Poundstone (Greg Kinnear), a character loosely based on L. Paul Bremer, he charges his forces to find Al-Rawi and the book before Miller can expose the charade that there are no WMD.

Green Zone touches on a number of key events surrounding the fall of Baghdad. That includes the disastrous dissolution of Saddam’s army in the hope of ridding it of his supporters (while not realizing that the army was also made up of terrified anti-Saddam forces who now found themselves justifiably angry and fodder for the coming insurgency), as well as the rejection of the corrupt Iraqi exile Ahmed Chalabi as the replacement for the deposed despot. But rather than dramatize the folly of American exceptionalism in its sweeping desire to bring democracy to Iraq, as the superb documentary

No End in Sight (2007) did,

Green Zone gets caught up in the tired story of one man trying to uncover the truth.

Greengrass is usually a master at blending suspense techniques with documentary realism – as he demonstrated in the last two

Bourne movies – but here, watching Miller dashing down the dark streets of Baghdad, the action ends up muddled and indistinct. (Miller might not find any WMD but he sure knows how to find his way down dark alleys in a strange city.) Damon gives a competent action performance, but there are no undercurrents to his conflict. He may not want to be lied to by officials, but you never get a sense of what he stands for beyond that. Greg Kinnear makes a great bureaucrat, but he’s conceived in callow terms that don’t come close to capturing the blind arrogance of Bremer. Brendon Gleeson brings some of the sneaky humour that Geoffrey Wright brought to his company man in

Casino Royale (2006), but he soon disappears from the film.

A number of critics have lazily suggested that the faults of this picture are due to Greengrass copying the template of his

Bourne movies, but the comparison is superficial. (Besides, unlike Miller, Bourne is an amnesiatic operative trying to recover his memory of being part of a clandestine element of the CIA.) Greengrass does, however, ultimately lose touch with the stronger elements of the story. He abandons the engaging political tumult for cheap melodrama - and the movie flags. Miller might heroically uncover a lie, encouraging the audience to cheer, but he still gets nowhere close to the truth. In its attempt to rouse indignation,

Green Zone ends up in a dead zone.

-- March 14/10

In my book

Artificial Paradise: The Dark Side of The Beatles' Utopian Dream, I was trying to answer a question: How did a group like The Beatles, who wrote songs about love and helped to build a popular culture based on pleasure and inclusion, also attract hatred and murder. To do so, I realized that I'd have to answer another key question: Was The Beatles' utopian dream truly worth it?

Given that the state of the world, in the wake of the band's demise, is not the one they sung about - and hoped for - in "All You Need is Love," it was tempting to ask whether or not The Beatles truly mattered. I thought I was going to have to justify the group solely on the strength of their music until I came across, quite by chance, a book by Larry Kirwan called

Liverpool Fantasy (2003). In his book, Kirwan (who was the lead singer of a New York-based Irish rock group called Black 47), imagines England without the emergence of The Beatles.

Liverpool Fantasy is a dystopian, yet comical, look at the absence of The Beatles from history. It doesn't spare the reader, but it doesn't ridicule the dream the band created either.

In